Spring is finally here and Dr. Paul Johnson and his team of biologists from the Alabama Aquatic Biodiversity Center (The AABC) are gearing up for another season of rescuing the Southeast’s most vulnerable aquatic species from extinction.

The Southeast might be home to one of the world’s greatest concentrations of aquatic wildlife, but it is also one of the planet’s hotspots of species endangerment.

These species are not optional. Each is a thread in the ecological fabric that sustains us. Healthy rivers support our economy (think: drinking water supply, tourism, coastal fisheries) and our way of life (think: scenic beauty and outdoor recreation). So, biologists like Paul throughout the region aren’t just saving biodiversity, they are saving us.

The Alabama Aquatic Biodiversity Center (AABC) is one of several state- or federal-run facilities in the South for rebuilding populations of endangered species. It became fully operational in 2010. Despite a lean budget of roughly $350,000 per year and a staff of six, the center has already rescued several species from extinction. I write about these victories in my forthcoming book, Creeks to Coast.

Paul and his staff specialize on freshwater snails and mussels. The Southeast (and Alabama in particular) has more of these species than any other region on earth. Some have been lost to extinction, and many are endangered.

The team from the AABC does much of their work with aquatic wildlife during the warm season when species are most active. Field work nearly impossible during the winter because rivers are too swift, deep, cold, and muddy to safely work in. During this winter downtime, the team writes reports, submits grant proposals, analyzes data, and plans the next field season.

I recently spoke with Paul to learn about the upcoming 2021 season. Once again, they will be working with biologists across the Southeast on projects involving dozens of species. I asked Paul for highlights on several of the most important projects.

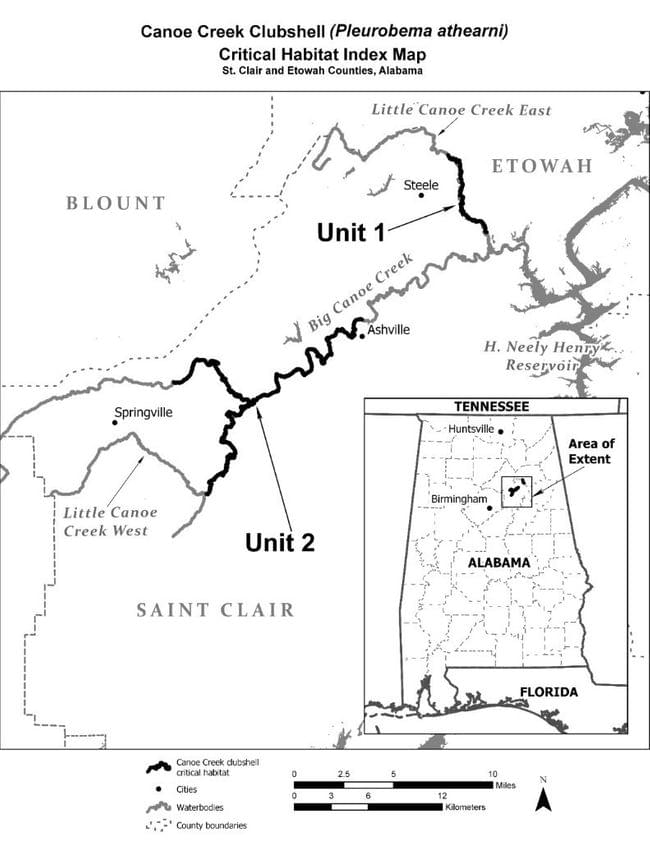

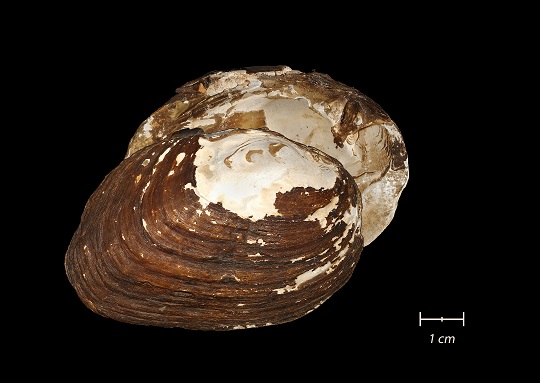

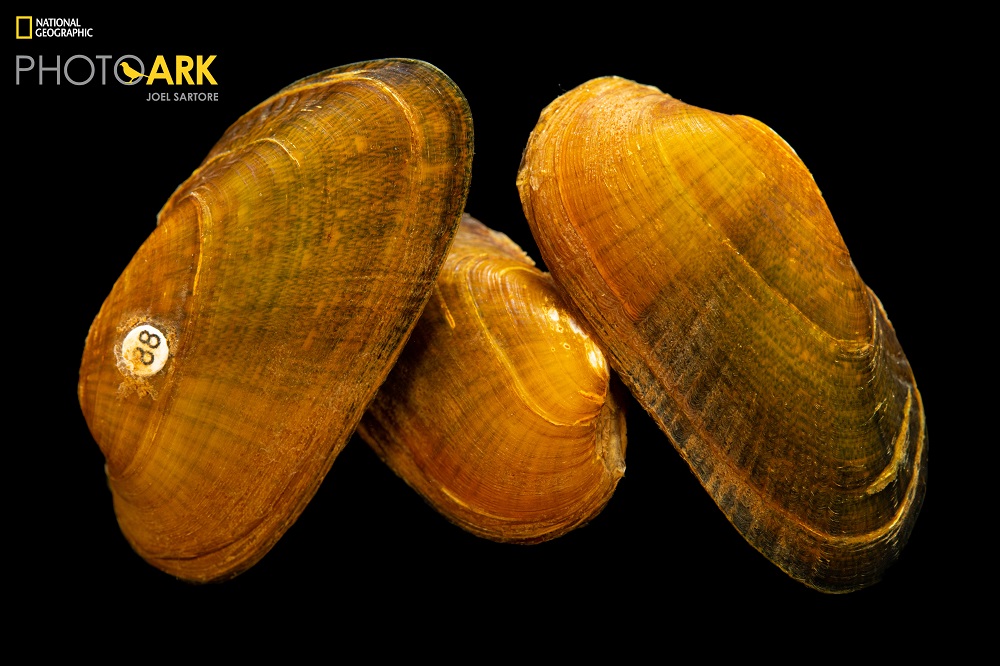

Canoe Creek Clubshell

One of the rarest mussels the AABC will be working with this year is unique to Alabama, the Canoe Creek Clubshell (Pleurobema athearni). The species is only known from a single watershed in northeastern Alabama. This, and the clubshell’s sparse population make it highly vulnerable to extinction. A single catastrophic event could wipe the mussel out completely. This isn’t a hypothetical. We’ve lost other mussel species this way.

Johnson’s team has been studying the clubshell for several years. Their discoveries contributed to a recent proposal to the US Fish and Wildlife Service to place the mussel on the Endangered Species List.

Getting federal protection for the species is important, but it isn’t enough to ensure the clubshell’s survival.

To that end, the AABC team has been working with various partners to bolster the mussel’s populations. That includes the US Fish and Wildlife Service, the Geological Survey of Alabama, local governments, and environmental groups such as the Friends of Big Canoe Creek and the Coosa Riverkeeper.

Already there’s been much progress. Most notably, the partnership removed a dam from Big Canoe Creek, the major artery of the watershed. Dams cause big trouble for river ecosystems. They block the seasonal migrations of wildlife. And the reservoirs behind dams smother stream habitats in mud and deep water. The removal of the dam restored wildlife habitat and reconnected stream sections separated for over a century.

This year, Paul’s team will be improving their technique for breeding Canoe Creek Clubshells in captivity. It’s a process known as culturing, and it’s essential to the recovery of the species.

Paul estimates there are fewer than 2000 clubshells in the wild. This isn’t enough to avoid inbreeding. Nor to protect the population against catastrophes. Through culturing, biologists raise young mussels at the AABC, then release them into suitable habitats within the natural range of the species. The work is not easy.

Biologists must find gravid females (those that have young larvae inside them). This can be difficult for rare species.

Then they must learn how to keep the female mussels healthy and happy in the lab with the right water chemistry, temperature, and food.

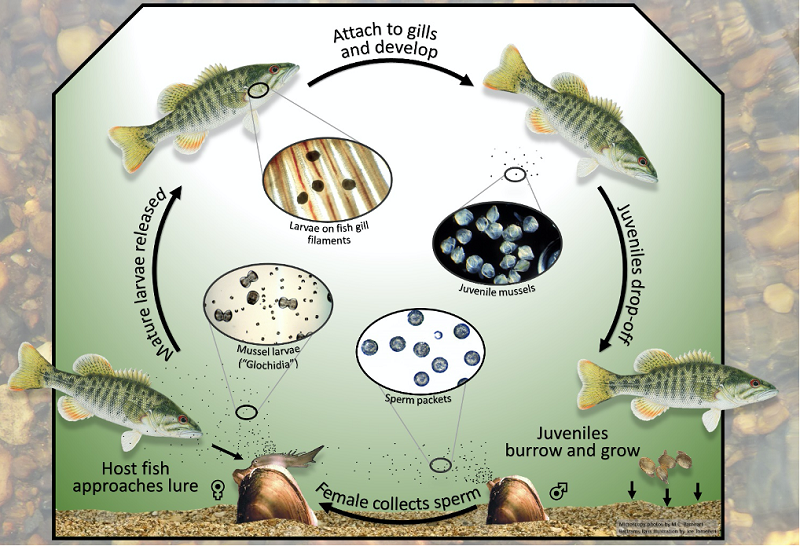

Next, they must introduce the correct fish species to the female mussels at the right time. Wait… fish? Yup. You read that right.

Freshwater mussels need fish to incubate their larvae until the young mussels can settle on the stream bottom. The larvae (called glochidia at this stage) must clamp down to the fish’s gills (sometimes fins) and hang on for several days to weeks as they draw nutrients from the fish host and grow.

The fish is mostly unharmed—it’s analogous to us catching a cold.

Most mussels have only one to several fish species that are appropriate hosts. The wrong host can reject the larvae with an immune response, or transport them into the wrong habitat.

Thus, most mussels have a method for tricking their target fish species into hosting their young. Canoe Creek Clubshells make small packets of glochidia resembling brightly colored worms. When released into the stream, the packets are the prefect size, shape, and color to attract small silvery minnows known as shiners. When a shiner takes a nibble, the packet explodes in the fish’s mouth releasing the glochidia. The glochidia then latch onto the gills of the fish.

Fortunately for the clubshell, several shiner species reside in the Big Canoe Creek watershed and are good hosts for their young. The bad news is that shiners don’t travel far, so this prevents young clubshells from settling in new habitats in the stream—new habitats like those restored by the dam removal.

This is where the AABC team can help. They extract glochidia from gravid females, then inject the larvae onto the fish’s gills. The fish are then monitored. When the mature larvae drop off, they are collected and raised until they are large enough for release.

The culturing process is slightly different for each species of mussel, and the biologists discover the best techniques through trial and error. That’s one of the things the AABC team will be doing this summer. They will also check up on the handful of cultured clubshells they released into a potential reintroduction site in Big Canoe Creek in 2020. If the young mussels are alive and growing, that site will be prioritized for the reintroduction of new batches of clubshells when they are ready.

Because the process is so involved, and the reintroductions must be coordinated with projects to restore stream habitats, the process of rebuilding a mussel population to where it is no longer endangered can take the better part of a decade or more.

Coosa Moccasinshell

An even more endangered mussel the AABC team will be working with this field season is the Coosa Moccasinshell (Medionidus parvulus). The mussel once occupied a huge region including the Black Warrior, Cahaba, and Coosa river watersheds of Alabama, Georgia, and Tennessee. But it has disappeared across most of its range, including all of Alabama.

Today, biologists find the Coosa Moccasinshell only in an 8-mile stretch of the Conasauga River that loops across the Georgia-Tennessee border, and a small adjacent tributary. That’s all that’s left of a population that once occupied thousands of stream miles in the region. Experts blame widespread mud pollution from erosion and habitat loss through damming.

Even within its current range the moccasinshell is rare. Paul Johnson estimates there are fewer than 1000 remaining in the wild. Consequently, the AABC and their partners (the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency and Georgia Department of Natural Resources) have trouble finding gravid females. This limits the culturing of new mussels for reintroductions. Early each spring they begin searching, but often find none.

But 2021 might be a big year for the Coosa Moccasinshell. In early March biologists found five gravid moccasinshells—far more than expected. “I’ve never seen that many gravid individuals at a single time – ever!” said Paul.

The AABC team has already captured the darters that they will use as hosts for culturing moccasinshell larvae. If they are successful, the AABC should be able to release the young mussels by fall 2022.

The release site will be the Little Cahaba River in Bibb County, AL. This is over 200 miles away from the Conasauga population, and that’s smart strategy. Establishing separate populations within the historic range prevents a single catastrophe from wiping out the entire species.

Nature's water filters

Mussels like the clubshell and moccasinshell deserve to survive because earth is their home, too. But they are also useful to us. Think of them as living water filters. Dirty waters goes in—laced with algae and sediment—and clean water comes out. The algae and other plankton are eaten, and the sediment is deposited on the stream bottom. Long ago mussel populations kept creeks and rivers running clear. Rebuilding their populations gets us closer to restoring rivers so they can provide the ecosystem services on which we depend.

Restoring the populations of rare species helps stream ecosystems resist threats and rebound after a disruption (I wrote about the importance of ecosystem resistance and resilience in this recent post). The more species present in an ecosystem, the more species are available to fill in the gap when one or more species suffers a setback. This is why extinction permanently damages ecosystems.

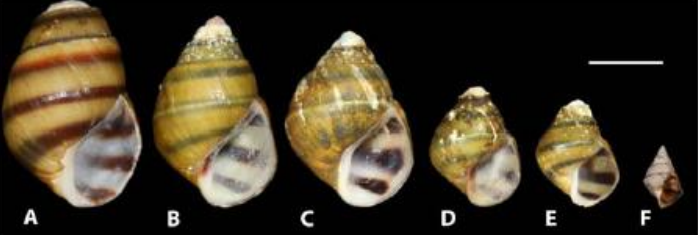

Oblong rocksnail

The Alabama Aquatic Biodiversity Center also cultures rare snails for species restoration.

Freshwater snails have also had a tough time surviving in the modern Southeast. Just in the Mobile River Basin, the largest watershed in the region, we wiped out 37 snail species last century. Many others species were exterminated from the basin but survive elsewhere.

For decades, one of those extinct snails was the Oblong Rocksnail (Leptoxis compacta), a tiny species known only from the Cahaba River. No one had seen the species since 1935.

Then in 2011, University of Alabama graduate student Nathan Whelan rediscovered the Oblong Rocksnail while surveying the Cahaba River. The news of the rediscovery was celebrated widely and attracted national media attention.

But the rediscovery didn’t ensure the snail could survive. Whelan was unable to find the rocksnail at seven other locations where it had been collected decades before.

In a research paper co-authored by Nathan Whelan (Director of US Fish and Wildlife Service’s Southeast Conservation Genetics Lab), Paul Johnson, and Phil Harris (Curator of Fishes, University of Alabama Museum of Natural History), the authors stated that “Because of its restricted range, L. compacta should be the focus of immediate conservation attention.” The Fish and Wildlife Service is now reviewing whether to place the rocksnail on the endangered species list.

Since then, the AABC has been honing techniques for culturing the species. They’ve now got a suitable protocol and 200 snails to work with as brooders. They’re hoping to breed them this summer.

By June they’ll know if their efforts are successful.

If you are wondering if freshwater snails offer anything of practical value, you can think of them as lawnmowers for a stream. As snails glide along rocks and logs, they scrape off and eat the layer of algae and other organisms growing on these surfaces. Without snails the steam bottom becomes a nasty shag carpet of slime. That’s bad for stream wildlife. And it’s gross for anyone who visits the stream.

* * *

These are just a few of the projects the Alabama Aquatic Biodiversity Center team will be working on this year. They will also be completing a four-year statewide survey of freshwater snails (117 species and counting!), describing for science newly discovered species of snail, helping Auburn University scientists develop molecular techniques for assessing mussel health, and monitoring populations of reintroduced snails and mussels. AABC does most of this work with universities and state and federal wildlife agency partners across the South.

So, although the Southeast is in an extinction crisis, it’s reassuring to know that biologist like those at the AABC are working to save as many of these species as they can across the Southeast.

Special thanks to Dr. Paul Johnson at the Alabama Aquatic Biodiversity Center for the information and many of the images in this post.

How to help

There are many ways you can help save our aquatic biodiversity in Alabama and throughout the Southeast. Here are a few…

- Buy an Alabama, Georgia, or Tennessee fishing license. The funds support programs like the Alabama Aquatic Biodiversity Center and other non-game conservation efforts in these states. You don’t have to ever go fishing, nor do you need to be a state resident.

- Don’t want a fishing license but own a vehicle? Purchase a conservation-themed license plate. Funds support non-game wildlife programs. Click for Alabama, Georgia, and Tennessee.

- Support local environmental groups that promote clean rivers for people and biodiversity. Become a member, sign up for their emails and newsletters, and heed their calls to action. Important groups for this story include…

If you have suggestions on how others can help, reach out to me and share your ideas!