The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) will soon decide the fate of the Apalachicola River ecosystem—arguably the wildest and most endangered river ecosystem in the eastern United States.

If I could stand before the nine justices and share a single lesson from the science of ecology to inform their decision, it would be this…

Healthy ecosystems are assets for humanity. Sick ecosystems are liabilities.

When ecosystems thrive, we thrive. Ecosystems purify our water and air. They provide us with food, medicines, fuel, and materials. They protect us from nature’s extremes such as droughts and storms. These benefits are known as ecosystem services.

Healthy ecosystems also take care of themselves. When there is a disruption such as a storm or heat wave, healthy ecosystems resist, survive, and recover quickly. Resistance and resilience are textbook indicators of healthy ecosystems.

Two things keep an ecosystem healthy: a proper supply of resources and an ecosystem’s biodiversity. Resources such as water, nutrients, and energy, are the ingredients for sustaining life. Biodiversity—the variety of species in the ecosystem—forms a web of relationships in the ecosystem through which these resources circulate.

Ecosystems grow weak when there is too much or too little of a resource, or when species disappear for unnatural reasons. Such ecosystems lose resistance and resilience. Subsequent disruptions cause more species to disappear and more resource imbalances. Left unchecked, this decay spiral continues until the ecosystem loses any resemblance to its original state and can no longer provide the ecosystem services on which we once depended.

Apalachicola Bay is in a decay spiral. And right now, the best hope for a rescue is with the Supreme Court.

A drought-induced Coma

In Part I of this post, I explained how several decades of increased water withdrawal for Metro Atlanta and for farms in southeastern Georgia had degraded the Apalachicola River Ecosystem. With the help of retired Riverkeeper Dan Tonsmeire we learned how the shortage of freshwater at the coast was causing the unravelling of the river ecosystem, from floodplain swamp forests to the oyster reefs, seagrass meadows, and saltmarshes of the estuary. During my interview with Dan, he explained that the events leading up to the 2013 collapse of the oyster fishery in Apalachicola Bay.

In 2007 a two-year-long drought settled over the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint (ACF) river basin. In the past, Apalachicola Bay habitats were more resistant to drought damage, and more resilient to the damages incurred. But decades of declining freshwater flows to the bay had worn down these defenses.

In addition, droughts in the Southeast have become especially hazardous for aquatic ecosystems in recent decades because human water consumption actually increases during times of water shortage. This can seem counterintuitive. We should use less water during a drought, not more.

When the rains disappear, farmers irrigate more to save their crops. Homeowners water their lawns more. And because summer droughts are associated with unusually high temperatures, the use of air conditioning increases. This causes thermoelectric powerplants (coal, gas, and nuclear) to use more river water to keep up with the demand for electricity.

Dan Tonsmeire explained that when the drought ended in early 2009, freshwater flows to the bay began returning to their normal pattern. Surviving oysters and other creatures began growing and reproducing again.

But in 2011—just two years later—another drought struck before the recovery was complete.

Lacking the resistance and resiliency the estuary once had, this drought sent the bay into a coma. The decline in river flow greatly reduced the supply of nutrients to the bay. Without nutrients, the bay’s plankton populations crashed. Guess who eats plankton? Oysters. Plus dozens of other estuarine species.

The scarcity of freshwater also allowed salty water from the Gulf to infiltrate the bay.

The high salinities stressed the physiology of the oysters, and the salty tides brought legions of oyster predators and parasites that normally stay away because they like salty marine waters.

The aftermath

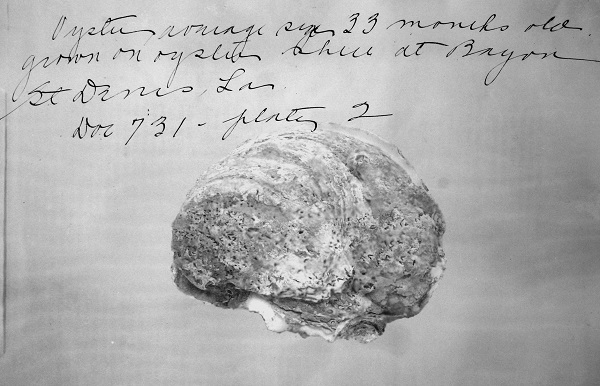

As a result of the drought, the oyster harvest declined precipitously in 2012. Scientists studying oyster populations saw declines they’d not seen in decades of monitoring.

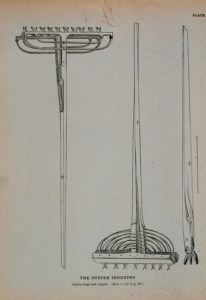

At first oyster fishers spent more time on the bay trying to make up for the lower harvests. But they mostly pulled up dead shells from the reefs. Before the drought, 200-300 oyster boats would be on the bay on an average day. By the end of 2012, fewer than 20 boats would go out. Most fishers quit trying. Fishers hauled their boats ashore, seafood processors laid off workers, and family breadwinners sought other income sources or filed for unemployment. Non-seafood related jobs are hard to find in this remote area.

For the next few years everyone waited for the oyster population to recuperate. It never happened.

In 2020, the State of Florida took an unprecedented step and closed the oyster fishery in the bay for five years. The State hopes this will give oyster populations enough time to rebound, and give scientists time to find solutions.

What has happened to the Apalachicola River Ecosystem is what happens when we push an ecosystem too far. In this case, years of declining freshwater flows stripped away the bay ecosystem’s capacity to resist drought and rebound.

The bay and the oyster fishery has entered a decay spiral. A team of marine scientists concluded in 2015 that:

“Although the Apalachicola Bay oyster fishery has proven resilient over its >150-year history to periods of instability, this fishery now seems to be at a crossroads in terms of continued existence and possibly risks an irreversible collapse.”

The drought hurt other species, too. Dozens of fish and shellfish species dependent on the oyster reefs, seagrass meadows, and salt marshes also became scarce. Their ranks include economically important species such as the Blue Crab.

With Apalachicola Bay now subjected regularly to saltier marine water, is it possible the estuary could undergo an ecological transformation and emerge as a thriving saltwater bay like many of the other bays of the northern Gulf Coast?

Nope. As emeritus Riverkeeper Dan Tonsmeire explained during the interview, such a conversion isn’t possible. Because the watershed is so large, and the southeastern climate so variable, there will always be rainy years when pulses of freshwater flow through the bay and kill off the marine species that establish.

Too salty for estuary species, and too fresh for marine species. Like the Apalachicola River swamps, the bay is spiraling into ecological purgatory.

Implications of the supreme court Decision

I won’t venture into the details of the dispute between Florida and Georgia. The case is convoluted and has been nicely summarized elsewhere for those of us lacking legal expertise.

Suffice it to say that a firm decision by the Court in favor of one side or the other will affect the economy and ecology of the region for decades to come.

A decision in favor of Florida will give Apalachicola Bay a fighting chance. The Supreme Court would likely order Georgia and the Army Corps of Engineers (the Corps manages many of the dams on the Chattahoochee River) to release more water to Florida. This would help the Apalachicola River Ecosystem recover. With time and careful management, the oyster fishery should be able to reopen. This would benefit hundreds of families whose lifeways depend on a healthy bay.

However, such a decision would impose hardships on Georgians, especially farmers in the lower ACF who irrigate their crops. For decades the State of Georgia has not imposed limitations on how much water they can withdraw. With a SCOTUS decision in favor of Florida, Georgia would likely impose limits on irrigation, especially during drought years. This could weaken the financial security of the thousands in the region with livelihoods tied to agriculture.

A SCOTUS ruling in favor of Florida could also impact residents of Metro Atlanta. If less water is withheld for the city in the reservoirs of the upper ACF watershed, then Atlanta would need to acquire new water sources or implement new water efficiency and conservation strategies. Depending on implementation policy, this could lead to higher utility bills for the area’s residents, an outcome that would be especially burdensome on Metro’s poorest families.

On the other hand, if the Supreme Court rules against Florida, Georgians will have an easier time maintaining their water supply, but the Apalachicola River Ecosystem will never pull out of its decay spiral due to a new ecological force shaping the ecosystem.

Climate Change and the ACF

Climate change is enhancing the threats to the Apalachicola River Ecosystem, especially the bay and habitats in the river delta. Rising sea levels are bringing salty ocean tides higher into estuaries than any time in the past several thousand years.

Meanwhile, rising temperatures are causing higher rates of evaporation across the region. Consequently, scientists predict that summer river flows in the ACF will decline by at least 9% this century unless global carbon dioxide emissions drop to net-zero.

Scientists also predict that climate change will cause more frequent and longer droughts in the Southeast. By some measures, this is already becoming the new normal.

Finally, the warming atmosphere is boosting the strength and size of hurricanes. Hurricanes can inflict considerable damage to estuaries. First, they flood them with a storm surge and destructive waves. Then, river floodwaters—thick with mud and low in oxygen—can suffocate marine life.

The best way to help the Apalachicola River Ecosystem recover from past damage and prepare it for the changing climate is to send more water down the river. The same is true for other river ecosystems in the Southeast.

River water can push back the salty tides and strengthen habitats like marshes and oyster reefs that protect the coast from sea level rise and sustain fisheries that employ and feed thousands of people. It’s time we start managing freshwater and other natural resources in ways that are regenerative, not exclusively extractive. We must prepare the region for the changes that are coming.

Healing the River

Considering all the challenges, it would be easy to be pessimistic and give up on the Apalachicola Bay Ecosystem. But one of our most important tasks this century involves building healthier relationships with our ecosystems. Fortunately, we have solutions for fixing the Apalachicola problem. Solutions that benefit everyone involved—from fishers, to farmer, to oysters. Healing southeastern rivers and adjusting to the new realities of climate change is a primary focus in my forthcoming book Creeks to Coast.

For the Apalachicola River Ecosystem, healing begins by recognizing that oysters and other estuarine species have narrow ranges of salinity tolerance, and this won’t change anytime soon. We humans are far more adaptable and it is our responsibility to change how much freshwater we use.

Governments can incentivize farmers to install irrigation systems that are more water efficient. Farmers can also use drought-resistant crops, no-till farming, and other practices that reduce water use. These new practices—already in use across much of the country—will help farms be more resistant and resilient to droughts and the longer, hotter summers the Southeast now endures. The barriers to implementation are financial and educational, not technical.

Similarly, we can be far more efficient in our use of water in cities. Atlanta has already made progress here. With a blend of new ordinances and financial incentives, the Metropolitan North Georgia Water Planning District has seen a 10% reduction in water use and a 30% reduction in per capita water use in recent years, even while the area’s population grew. There’s still much more the city can do, and these measures will help defend Metro Atlanta against the water shortages that worsening droughts will bring.

Fighting climate change in the Southeast will also help. Coal, gas, and nuclear power plants consume 26% of all the surface water withdrawn in the ACF basin. This is over twice as much as pulled from ACF streams by farmers. As we build wind and solar farms to replace coal and gas power plants (something we need to do ASAP to prevent the climate crisis from getting completely out of hand), this will leave more water in rivers for people and the ecosystems we rely on.

These multisolving approaches will get us out of the ecological mess we’ve created and help build a more prosperous and secure future for the people and other species who live in the Southeast. And the truth is, we should do this regardless of what the Supreme Court decides on Florida vs. Georgia.

***

Special thanks to Dan Tonsmeire for all he’s done for the Apalachicola River Ecosystem—its wildlife and people—and for sharing his knowledge with me.

How you can help:

You can be part of the solution, even if you don’t live in the ACF watershed.

- Enjoy eating seafood? Buy from Apalachicola. They oyster fishery is closed, but fishing families in are still harvesting blue crabs, shrimp, and fishes. Buying Apalachicola seafood helps sustain the people and the lifeways of Apalachicola and nearby towns.

- Visit Florida’s Forgotten Coast. The money you spend for local lodging, restaurants, and in local businesses helps sustain the community. The area is gorgeous and you will love your time there.

- Support the environmental organization in the region helping the river, the region’s people, and pushing for long-term sustainable solutions. You can start by supporting the Apalachicola Riverkeeper, the Chattahoochee Riverkeeper, and the Flint Riverkeeper. The Georgia River Coalition and the Georgia River Network endeavor to protect rivers and communities throughout the state.

- Live in Metro Atlanta? Learn from your Metropolitan North Georgia Water Planning District how you can help improve water efficiency and conservation in your home and your community.

- Are you a Georgia farmer or do you live in a farming community? Visit the Georgia Soil and Water Conservation Commission website to learn about how to adopt water conservation strategies.

Do you have other suggestions for how people can help the ACF recover? Reach out to me and share your ideas!